Two landmark surveys open in London this month. Donald Rodney, at the Whitechapel Gallery, and Noah Davis, at the Barbican Art Gallery, worked a generation apart but made vital contributions to contemporary art, both through their work and their organising in distinct cultures—Rodney in 1980s and 1990s Britain, Davis in Los Angeles in the 2000s and 2010s.

But they are also linked by tragedy. Both died young: Rodney, aged 36, in 1998, from complications relating to sickle cell anaemia; Davis at 32 in 2015 from liposarcoma, a rare cancer. These shows are likely to prompt echoes of Ezra Pound on the Modernist sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, who died at 23 in 1915: “A great spirit has been among us, and a great artist is gone.”

Rodney was a member of the BLK Art Group in the UK in the 1980s. After his death, fellow member Eddie Chambers wrote of Rodney in Third Text magazine, “it was probable—inevitable even—that Rodney would… become an artist of major significance, irrespective of how and in whatever direction his fledgling practice developed”.

Rodney had already shown the impact he could have with his 1989 exhibition Crisis. “Crisis” had three connotations. Two were political and are ongoing: the rise of right-wing politics and the environmental crisis. The third was deeply personal: crisis is a term used for a sickle cell attack. For Rodney, “the illness metaphor” was a decoding mechanism, since, he explained, “Within the society blacks are perceived widely as the disease within the body politic of Britain.” The works were made using oil stick on X-rays, a legacy of long periods in hospital. Britannia 3 Hospital (1988) is a partial self-portrait, with Rodney cared for by a nurse, and loomed over by a member of the Metropolitan Police’s notorious Special Patrol Group, next to a figure referencing Frida Kahlo’s Broken Column, but with the face of Cherry Groce, the innocent victim of a police shooting in 1985. The Crisis works were made on a placement at The Hub, a Sheffield community space that Rodney called “a Black centre”; they fulfilled a brief to address “issues involving a wide and diverse audience”.

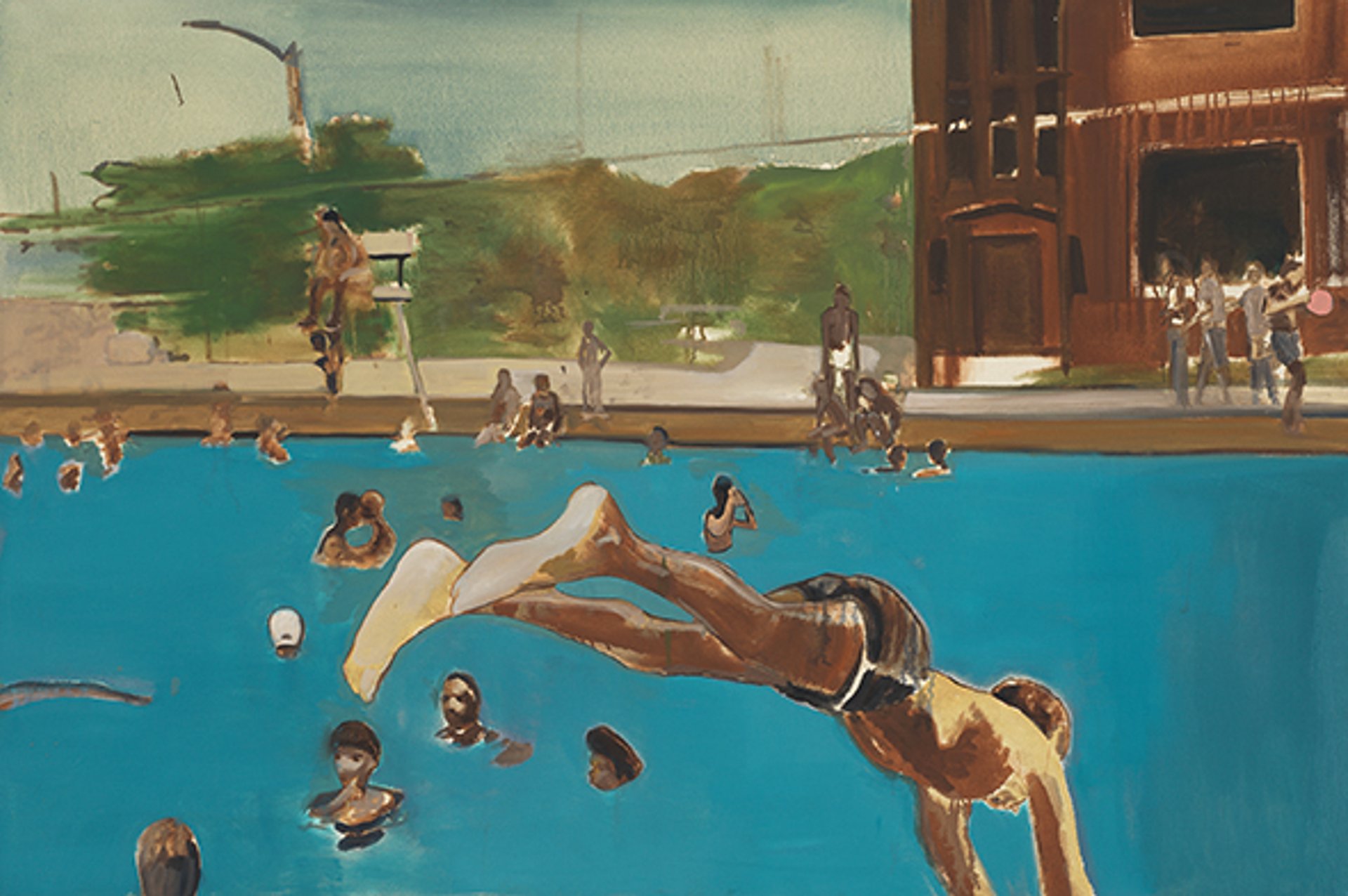

Noah Davis’s 1975 (8) (2013, detail). The Barbican Art Gallery’s exhibition dedicated to the painter opens on 6 February © David Zwirner

Davis, too, was committed to community. In 2012, he founded the Underground Museum (UM) in Arlington Heights, Los Angeles, with the artist Karon Davis, his wife. Its aim was to ensure “no one has to travel outside the neighbourhood to see world-class art, or learn from leading thinkers, educators, chefs and artists”. In common with The Hub, UM defined itself as “a Black space, but all are welcome”.

‘Normal scenarios’

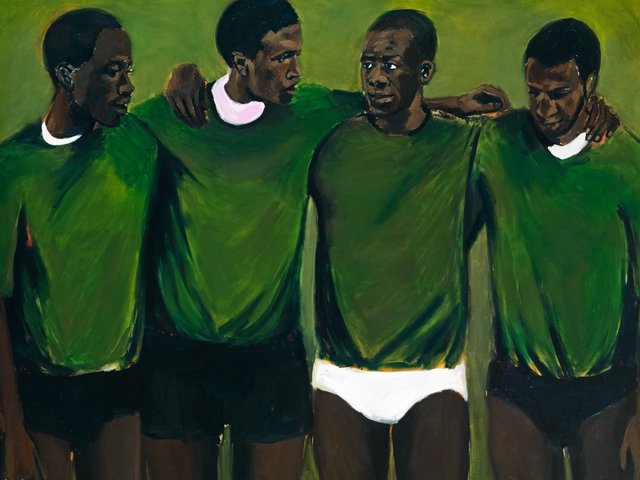

One major difference between the two artists was in Davis’s impulse regarding representing the community. “You rarely see Black people represented independent of the civil rights issues or social problems that go on in the States,” he said in 2010. He stated that his paintings “aren’t political at all” and wanted to show “Black people in normal scenarios”. The paintings he produced are remarkable in their evocation of these experiences, at once precise and yet elusive, redolent of the uneven focus of memory. In the exhibition catalogue, the poet Claudia Rankine describes them as “encircled by a realm of quiet, quiet joy, quiet sorrow or ordinary acceptance of our quotidian”. An act, I think, of profound political significance.

Rankine is among many luminaries and friends who contribute to the catalogue. It returns me to Ezra Pound, who described Gaudier as “incalculably great in promise and in the hopes of his friends”. That both Rodney and Davis are not just magnificent individual artists but sought a wider purpose only amplifies their achievements, however tragically short they were cut.

• Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 12 February-4 May

• Noah Davis, Barbican Art Gallery, London, 6 February-11 May